Can You Be Allergic to Air? The Truth About Modern Irritants

Key Takeaways

- You can't be allergic to air itself — but pollen, dust mites, mold spores, pet dander, and VOCs suspended in it cause allergic reactions in roughly 50 million Americans each year.

- Indoor air is two to five times more polluted than outdoor air, according to the EPA, making your home the most likely source of chronic allergy symptoms.

- If your "cold" lasts longer than 10 days, includes itchy eyes, and improves when you leave the house — it's probably an airborne allergy, not an infection.

- Keeping indoor humidity below 50% is the single highest-impact step you can take: it starves dust mites and stops mold growth simultaneously.

- Stacking an air quality monitor with a HEPA purifier and proper HVAC maintenance reduces total allergen load far more than any single measure alone.

Every spring, Google searches for "can you be allergic to air" spike by double digits. The short answer: no. Air itself — nitrogen, oxygen, argon — is immunologically inert. But the particles hitching a ride through it are a different story. The EPA estimates indoor air carries two to five times more pollutants than outdoor air, and for the roughly 50 million Americans dealing with allergies annually, that gap between "air" and "what's floating in it" is the entire problem.

What Are Airborne Allergens?

Airborne allergens (aeroallergens) are microscopic particles that trigger immune reactions when inhaled. Your body misidentifies them as threats and launches a defensive response — the sneezing, congestion, and itchy eyes people recognize as allergy symptoms.

Particle size determines where the damage happens. Pollen grains measure 10–100 microns and get caught in nasal passages, causing upper respiratory symptoms. Dust mite fragments run 10–40 microns. Mold spores shrink to 2–10 microns. PM2.5 particles and certain VOCs drop below 2.5 microns — small enough to bypass the nose entirely and reach deep lung tissue, triggering chest tightness and asthma flare-ups.

The most common culprits:

- pollen (trees, grasses, weeds),

- dust mites, mold spores,

- pet dander,

- cockroach droppings,

- and volatile organic compounds.

Some are seasonal. Others — dust mites, mold, pet dander — persist year-round indoors.

🚨One thing that surprises people: airborne allergies can develop at any age. A person who tolerated cats for decades can become sensitized after prolonged exposure. The immune system recalibrates constantly, and repeated contact with certain particles can trigger reactions where none existed before.

🚨One thing that surprises people: airborne allergies can develop at any age. A person who tolerated cats for decades can become sensitized after prolonged exposure. The immune system recalibrates constantly, and repeated contact with certain particles can trigger reactions where none existed before.

Sources of Indoor Air Pollution

People picture highway exhaust when they think about air pollution. But indoor environments consistently carry higher concentrations of many pollutants — a problem made worse by the fact that Americans spend about 90% of their time inside.

- Biological pollutants dominate. Dust mites colonize mattresses and upholstered furniture, feeding on shed skin cells and thriving above 50% humidity. Pet dander — microscopic skin protein flakes, not fur — stays airborne for hours and clings to HVAC ductwork long after the animal leaves. Mold grows wherever moisture accumulates: behind drywall, inside AC drip pans, around window frames.

- Chemical pollutants are the category most people miss. VOCs off-gas from paint, cleaning products, air fresheners, new furniture, and pressed-wood cabinetry. Gas stoves produce nitrogen dioxide at concentrations that routinely exceed outdoor standards.

- Particulate pollutants come from candles, fireplaces, indoor smoking, and high-heat cooking. These PM2.5 particles are too small for standard HVAC filters to capture and accumulate without any visible trace.

These sources compound each other. High humidity feeds dust mites and mold simultaneously. Poor ventilation traps VOCs and particulates together. Dirty HVAC filters recirculate everything through every room. That cocktail is why so many people with "mysterious" year-round symptoms eventually find the answer inside their own home.

What Is Bad Air Quality? Pollutants and Their Sources

Air quality is measured by the concentration of specific pollutants — not by how the air smells or looks. The EPA's Air Quality Index (AQI) tracks six criteria pollutants: ground-level ozone, particulate matter (PM2.5 and PM10), carbon monoxide, sulfur dioxide, nitrogen dioxide, and lead. An AQI reading above 100 is considered unhealthy for sensitive groups; above 150, it's unhealthy for everyone.

But AQI monitors sit outdoors. Indoor air quality has no standardized federal index, and that's where most allergic reactions happen.

|

Pollutant |

Common Sources |

Health Concern |

|

PM2.5 |

Cooking, candles, smoking, wildfires (infiltration) |

Penetrates deep lung tissue; worsens asthma |

|

VOCs |

Paint, cleaners, furniture off-gassing, air fresheners |

Eye/throat irritation; long-term respiratory damage |

|

Formaldehyde |

Pressed-wood products, insulation, certain fabrics |

Classified carcinogen; triggers allergic rhinitis |

|

NO₂ |

Gas stoves, space heaters, fireplaces |

Airway inflammation; increased infection risk |

|

Mold spores |

Damp areas, AC units, bathrooms, basements |

Allergic rhinitis, asthma attacks, sinusitis |

|

Biological allergens |

Dust mites, pet dander, cockroach debris, pollen |

Sneezing, congestion, itchy eyes, wheezing |

Two things stand out from that table. First, many sources are things people use daily without a second thought — scented candles, gas stoves, spray cleaners. Second, most of these pollutants are invisible. VOC concentrations can be 5–10 times higher indoors than outdoors, according to the EPA, without any obvious sensory cue.

Seasonal patterns add another layer. Spring and summer push pollen counts up, and opening windows to "get fresh air" often does the opposite — pulling pollen and outdoor PM2.5 directly into your home. Fall brings ragweed and decaying leaves that feed outdoor mold. Winter seals homes tight, trapping moisture and driving dust mite and mold growth while concentrating VOCs from heating systems and holiday candles.

What Symptoms Indicate an Airborne Allergy?

Airborne allergy symptoms overlap heavily with colds and sinus infections, which is why so many cases go undiagnosed for months or years. The difference comes down to pattern and duration.

Airborne allergy symptoms overlap heavily with colds and sinus infections, which is why so many cases go undiagnosed for months or years. The difference comes down to pattern and duration.

- Upper respiratory signs show up first in most people: persistent sneezing (especially in clusters), runny or stuffy nose, post-nasal drip, and itchy or watery eyes. These point to allergic rhinitis.

- Lower respiratory signs suggest smaller particles reaching the lungs: chest tightness, wheezing, shortness of breath, and dry cough that worsens at night. These symptoms often indicate allergic asthma or a reaction to fine particulates like PM2.5 and mold spores.

- Skin reactions are less common but telling. Eczema flare-ups, hives (urticaria), and general itchiness can all be triggered by airborne allergens — particularly pet dander and dust mite proteins. Cold urticaria, a specific reaction to cold air exposure, produces hives and redness within minutes and can escalate to anaphylaxis in severe cases.

- Systemic symptoms are the ones people rarely attribute to allergies: fatigue, headaches, difficulty concentrating ("brain fog"), and disrupted sleep from congestion.

⚠️Cold vs. allergy — the quick test: Colds include body aches and sometimes fever; allergies don't. Colds resolve in 7–10 days; allergy symptoms persist as long as exposure continues. If your "cold" lasts three weeks and gets worse when you're home, it's probably not a cold.

Pay attention to timing. Symptoms that flare in specific rooms, at certain times of day, or during particular seasons point directly to environmental triggers. Waking up congested every morning suggests dust mite exposure in bedding. Symptoms that improve when you leave the house and return when you come back are a textbook sign of indoor allergen sensitivity.

How to Diagnose Airborne Allergies?

Diagnosis starts with a medical history. An allergist will ask when symptoms occur, where they're worst, what makes them better or worse, and whether there's a family history of atopy (the genetic tendency toward allergic diseases).

From there, two primary tests confirm which specific allergens are responsible:

Skin prick testing is the most common method. An allergist applies tiny drops of allergen extracts — dust mite protein, mold spores, pet dander, various pollens — to the forearm or back, then lightly pricks the skin beneath each drop. If you're sensitized, a small raised bump (wheal) appears within 15–20 minutes.

Specific IgE blood tests measure allergy-causing antibodies in your bloodstream. Used when skin testing isn't practical — for patients on antihistamines that can't be stopped, those with severe eczema covering test sites, or people with a history of anaphylaxis. Blood tests take longer (days rather than minutes).

In some cases, allergists use nasal provocation tests — directly exposing nasal passages to a suspected allergen under controlled conditions — to confirm triggers that skin and blood tests leave ambiguous.

One diagnostic step people overlook: environmental testing. If allergy tests confirm dust mite or mold sensitivity, testing your home's humidity levels, checking HVAC systems for mold growth, or using an air quality monitor to track PM2.5 and VOC levels can pinpoint exactly where exposure is happening. Knowing you're allergic to mold is useful. Knowing the mold is behind your bathroom wall is actionable.

One diagnostic step people overlook: environmental testing. If allergy tests confirm dust mite or mold sensitivity, testing your home's humidity levels, checking HVAC systems for mold growth, or using an air quality monitor to track PM2.5 and VOC levels can pinpoint exactly where exposure is happening. Knowing you're allergic to mold is useful. Knowing the mold is behind your bathroom wall is actionable.

How to Prevent Airborne Allergies?

1. Humidity control is the single highest-impact change for indoor allergies. Dust mites can't survive below 50% relative humidity, and mold growth stalls without moisture. A dehumidifier in damp-prone rooms — basements, bathrooms, laundry areas — handles both. Air conditioning helps too, by pulling moisture from indoor air while keeping windows closed against outdoor pollen.

2. Cleaning routines — technique matters more than frequency. Wash bedding weekly in water above 130°F to kill dust mites. Use a vacuum with a HEPA filter — standard vacuums blow fine particles back into the air. Damp-dust surfaces instead of dry dusting, which just redistributes allergens. Replace carpet with hard flooring where possible, especially in bedrooms.

3. HVAC maintenance is the one most households neglect. Change filters every 60–90 days (monthly during high-pollen seasons or if you have pets). Filters rated MERV 11 or higher capture pollen, dust mite debris, and mold spores. Have ductwork inspected for mold if you notice musty smells when the system runs.

4. Behavioral adjustments — shower and change clothes after extended time outdoors during pollen season. Keep pets out of bedrooms. Remove shoes at the door — they track in pollen, mold spores, and particulates. Check local pollen forecasts and keep windows closed on high-count days.

What Are the Treatment Options for Airborne Allergies?

When prevention isn't enough, treatment escalates in tiers.

Over-the-Counter Medications

Antihistamines (cetirizine, loratadine, fexofenadine) block histamine receptors and relieve sneezing, itching, and runny nose. Second-generation versions cause less drowsiness than older options like diphenhydramine. For nasal congestion specifically, corticosteroid nasal sprays (fluticasone, mometasone) reduce inflammation directly where it occurs and are considered first-line treatment for moderate-to-severe allergic rhinitis.

Prescription Options

For symptoms that resist OTC management. Leukotriene receptor antagonists (montelukast) target a different part of the inflammatory pathway. For allergic asthma triggered by airborne allergens, inhaled corticosteroids and bronchodilators manage airway inflammation and constriction.

Immunotherapy

The closest thing to a long-term fix. Allergy shots (subcutaneous immunotherapy) expose the immune system to gradually increasing allergen doses over 3–5 years. Sublingual immunotherapy — dissolvable tablets placed under the tongue — offers a needle-free alternative for specific allergens like grass pollen and dust mites. Both approaches can reduce symptom severity by 30–50% and, in some cases, produce lasting tolerance even after treatment stops.

Environmental Monitoring

Tracking indoor pollutant levels — particularly TVOCs (total volatile organic compounds), PM2.5, and humidity — helps you identify spikes before symptoms escalate. If you know VOC levels surge every time you cook or clean, you can ventilate proactively rather than react after the headache starts.

How to Increase Air Quality in Your Home

Preventing allergies is one thing. Actively improving the air you breathe is another — and it requires knowing what's in it first.

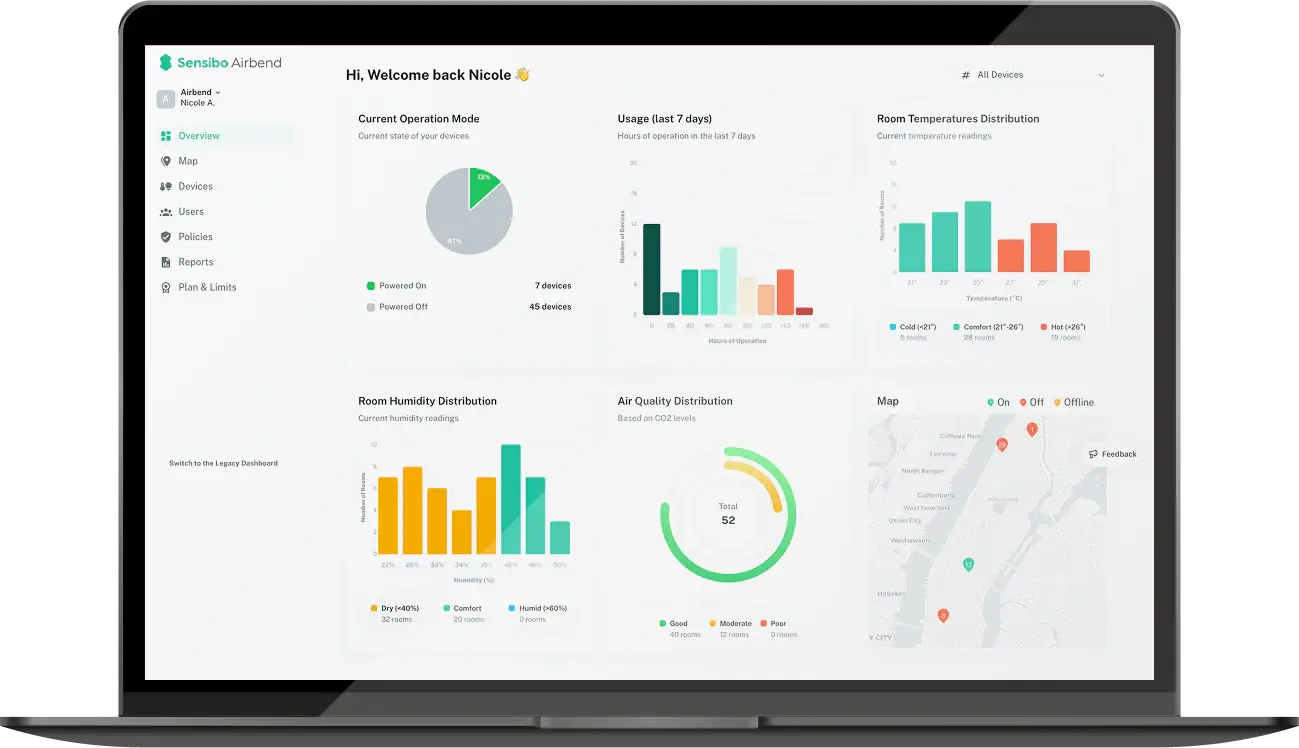

You can't fix what you can't quantify. An indoor air quality monitor that tracks PM2.5, VOCs, CO2 equivalent, and humidity gives you a baseline and shows how daily activities — cooking, cleaning, running the dryer — shift conditions in real time. The Sensibo Elements monitors six parameters including TVOC, ethanol vapors, and particulate matter, displaying aggregate air quality scores through a color-coded LED so you know at a glance when levels spike.

Once you see the data, act on it. A HEPA air purifier removes 99.97% of particles down to 0.1 microns — pollen, dust mite debris, mold spores, pet dander, smoke, bacteria. Place it in the room where you spend the most time, typically the bedroom. The Sensibo Pure pairs HEPA filtration with smart controls, and its PureBoost feature automatically ramps up purification when an Elements monitor detects declining air quality — no manual adjustment needed.

Beyond monitoring and purification, a handful of habits close the remaining gaps:

Beyond monitoring and purification, a handful of habits close the remaining gaps:

- Open windows early morning or late evening when pollen counts drop — not midday

- Run exhaust fans while cooking and 15–20 minutes after to clear NO₂ and PM2.5

- Fix water leaks within 48 hours; mold colonizes damp surfaces fast

- Switch spray cleaners and air fresheners for low-VOC or fragrance-free alternatives

- Store household chemicals in sealed containers outside living spaces

- Run bathroom fans during and after showers to prevent humidity buildup

No single device or habit eliminates indoor air pollution on its own. Monitor, purifier, humidity control, source reduction — they compound. A monitor identifies the problem. A purifier handles particulates. Humidity control starves biological allergens. Stack them and your total allergen load drops to the point where symptoms ease.

FAQ

Can you be allergic to air itself?

No. Air — the mixture of nitrogen, oxygen, and argon — doesn't cause allergic reactions. What triggers symptoms are particles suspended in the air: pollen, dust mites, mold spores, pet dander, and volatile organic compounds. The distinction matters because treatment targets these specific allergens, not the air itself.

What is air conditioning sickness?

Not a medical diagnosis, but a common term for symptoms that flare when the AC runs — sneezing, congestion, headaches, fatigue. Usually caused by allergens or mold circulating through a dirty system, or by excessive dryness irritating nasal passages.

What are the most common airborne allergens indoors?

Dust mites, mold spores, pet dander, cockroach droppings, and VOCs from household products. Unlike seasonal outdoor allergens like pollen, these are present year-round and can cause persistent symptoms that people often mistake for recurring colds.

Can you develop airborne allergies as an adult?

Yes. Adult-onset allergies are common. Relocating to a new climate, adopting a pet, living in a water-damaged building, or cumulative exposure over years can all trigger sensitization. If you've never had allergies before and start experiencing persistent respiratory symptoms, an allergy panel is worth pursuing.

Can air conditioning cause allergies?

Air conditioning doesn't cause allergies, but a poorly maintained AC unit can circulate allergens.

Can air pollution make allergies worse?

Yes. Air pollutants like ozone, nitrogen dioxide, and PM2.5 inflame the respiratory tract, making it more reactive to allergens. Research shows people exposed to higher pollution levels experience more severe allergy symptoms.

Do air purifiers help with airborne allergies?

HEPA air purifiers remove 99.97% of airborne particles down to 0.1 microns, which covers the major biological allergens. They're most effective in enclosed rooms with doors and windows closed. Pairing a purifier with an air quality monitor lets you verify the improvement rather than guessing.

What humidity level prevents dust mites and mold?

Below 50% relative humidity. Dust mites dehydrate at lower levels, and mold requires moisture to colonize surfaces. A dehumidifier, proper ventilation, and air conditioning all help maintain this range.

.jpg?height=200&name=photo_2023-12-29_20-01-46%20(1).jpg)